For 10 days in May of 1973, the world waited as NASA worked hard to prepare a fix to the damaged Skylab space station. Based on the information available, they knew what kind of damage had happened to the station during launch, but without being up there to see it, no one knew quite for sure just how bad off Skylab was.

Two problems needed to be addressed – the heat building in the station due to the loss of the micro meteoroid shield, and freeing the damaged solar wing so that the station could actually have enough power to function for the longer duration missions planned for it later in 73 and into 74.

A crippled space station…

The first manned mission could, in theory, run off the fuel cells in the Apollo Service Module. These hydrogen-oxygen reaction system generated electricity in the Apollo spacecraft for the Moon missions they were originally designed for, and depending on drain could function for several weeks, generating power. Of course, these fuel cells had limits, and while the 1st manned mission to Skylab, planned for about 28 days, could have used the CSM power supplies to supplement the power Skylab was generating, this wouldn’t work for the later missions, both due to limits on the Apollo fuel cells capabilities and the damage that would be done to the batteries on Skylab by it operating for months on end under such power-starved conditions.

That was all meaningless though unless the temperatures could be brought down in the station. The heat was slowly destroying supplies onboard, and was far too high for a crew to safely live and work in the station. There were also risks of toxic gases being released in the station by the breakdown of some of the materials stored onboard, which would pose their own risks to the crew. Some kind of shade had to be designed and deployed, on orbit, yet be able to be packed inside of the relatively tight space of the Apollo Command Module.

As it would turn out, the solutions to these problems would be somewhat simple. For the solar shade, there was originally a plan of a specialized “Mylar” blanket to be draped over the station and secured in several spots to the Orbital Workshop. This, however, proved to be complex to implement as planned, requiring a very complex and risky spacewalk from the Skylab 2 crew. The sun shade, to some, seemed like a lost cause until NASA engineer Jack Kinzler realized there was a scientific airlock on that side of the station which could be used as a deployment point for an umbrella (or, more accurately, parasol) like shade assembly.

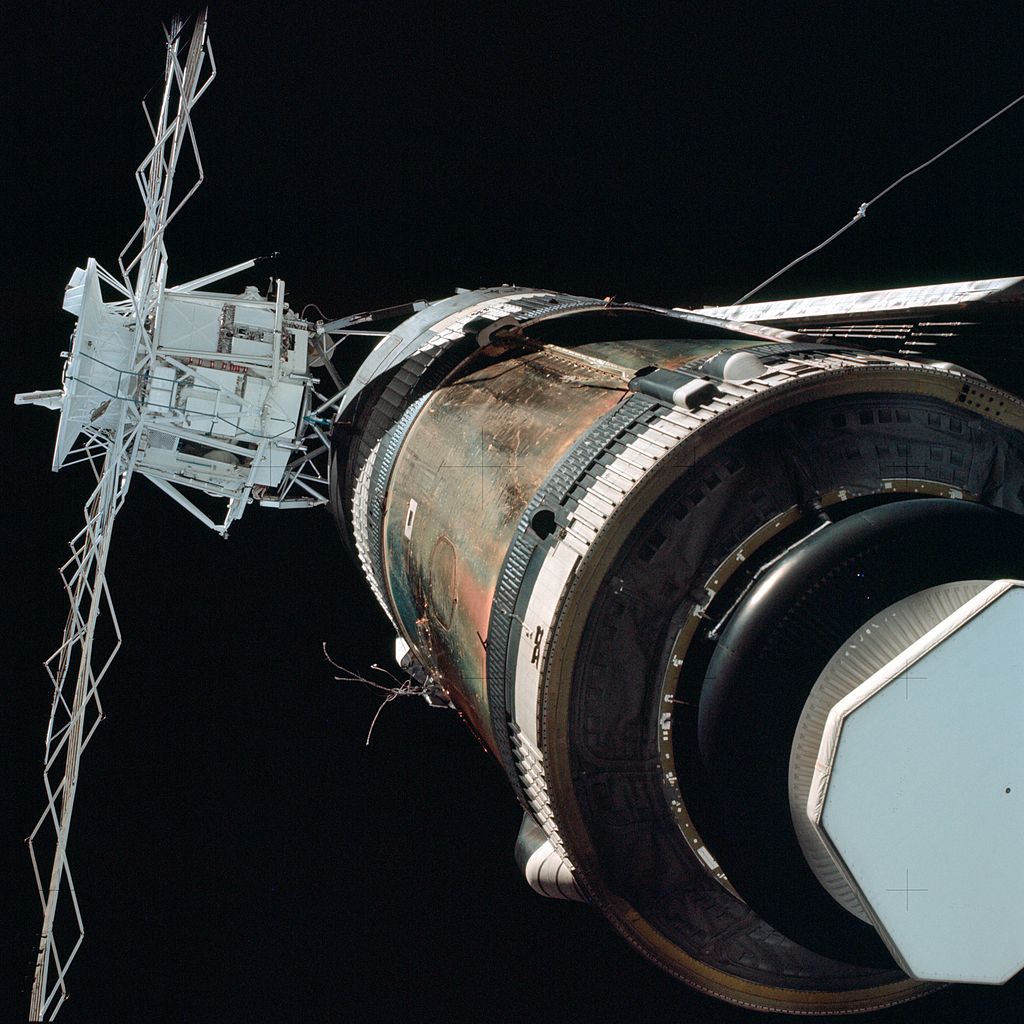

The airlock that the Skylab sunshade would be pushed through. Note the damage to the station hull.

The next manned mission was packed with both types of shades with the first shade planned to be deployed being the “parasol shade.” So long as the crew could safely enter the station, this looked like it would work.

As for the sole remaining, stuck solar wing, it was presumed to have become tangled up in debris, namely a set of straps which would need to be cut. NASA engineers eventually chose what amounted to a telephone company lineman’s pole shears. A simple but, based on what was known and presumed to be wrong on the station, effective solution. Cut the debris and the solar wing should open up fully and begin generating power for the station as best it could.

This equipment all would fit in the Command module for the first Skylab mission, and with quite a bit of additional training and mission changes, it looked like we would have a good chance at saving the station. Skylab 2 would become an orbital repair mission.

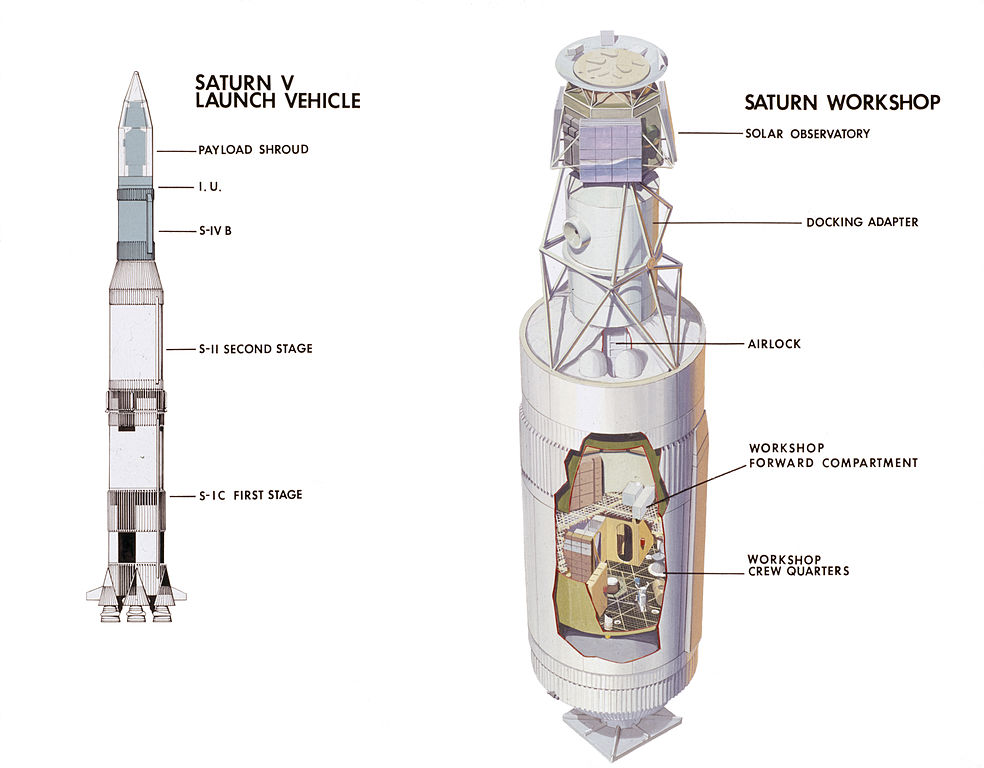

A diagram of Skylab as it was in launch configuration.