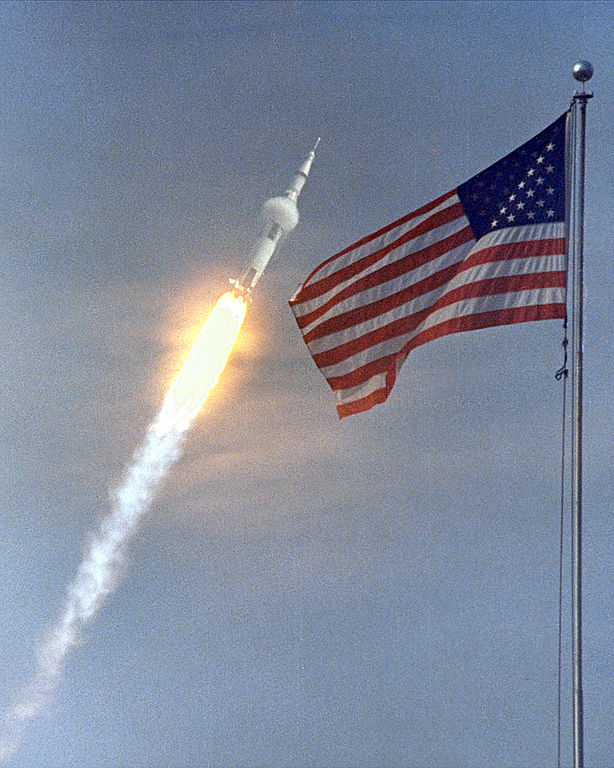

The evening of July 20th was spent with me watching the entirety of the Apollo 11 moonwalk as it had happened 50 years ago on that same date. I knew the whole event was only about 2 hours long but, like everything about watching the mission in real time, it was amazing to me how it just happened, then ended. Such a short stay compared to the ones in later missions, it just helped cement how this was a first event in history, and how many more were to (and should have) happened following that.

As I’ve devoted the past few days to thinking about Apollo 11 and capturing my thoughts on the 50th anniversary a common theme is the above — how all the events just “kind of happened” as they did. That’s how life works, but historic events are interesting in that, when they are talked about in documentaries or dramatized in television and film, they are all segmented into the most interesting or most important parts, with the filler left out.

It distorts our understanding of things — sometimes documentaries spend more time focused on a particular moment than the length of time the moment actually was! Other times, things are glossed over in such a way as to make them seem like like they were nothing when they may have taken hours (such as preparing for the EVA following landing.)

What I’m getting at is we don’t think of the events as they actually happened — we think of them more like how they are presented in those programs we watch, so when you see it happen as it did, in complete context, it changes how you think of it — it becomes real, and for someone like me who was born well after the Apollo program was finished it was a very special thing to follow it as I did.

As has much of the world. While, as I write this, the mission anniversary isn’t over, this time 50 years ago the Apollo 11 crew was well on their way back to Earth, the key elements of the mission being accomplished. We had done what many thought was impossible, and all that remains was the by then relatively mundane activity of re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere and splashdown in the Pacific.

As soon as the landing had happened, though, NASA’s budget would be cut. Missions would start being scrapped, some of the resources freed up being put into what would become SkyLab, and with the addition of the failure of Apollo 13 our days on the Moon would be numbered.

It wasn’t all a loss, though — NASA would remain and even under a tight budget would get the Space Shuttle operational by 1981 with mixed results in retrospect – a wonderful idea that had critical flaws, to describe it in short form. Still, the shuttle was a legacy element of Apollo, one of thousands of direct improvements to technology and life that were spawned by the goal of getting people to the Moon. Things that we use daily created by this effort, and most don’t know it — something many saw as a waste after the first landing had proved event then, as it does now, to have advanced us as much, if not more, than any war or any other peacetime effort had.

What saddens me is that this is probably the last time anyone will care about space history in my time. Sure, they may pay a bit of attention to the 50th anniversary of Apollo 13 in a few months, but just as they didn’t care about the Apollo missions before 11 they probably won’t care after 11 either, much like how in 1969-1970 the public had regarded space flight as “routine” and “boring.” All they will care about is new stuff, mainly from a certain over-hyped group which shall remain nameless, only looking for the neat show presented, understanding nothing about how any of this works, why it works, what it’s all for, or really caring about any of the reality of ti all — it’s all hype and style to generations these days, and it sickens me.

Appreciation for the grandness of it all. Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and the Soviet programs, Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz, it’s lost to all but a relatively small group of us. Even as I write this, in between the early half and what I’m finishing with now I learned of the death of Christopher Kraft, a man instrumental to the U.S. Manned Space Program, and someone I had an incredible respect for as a part of this achievement. It’s quite the painful reality to face, much like the loss over the past few years of John Young, Gene Cernan, or John Glenn, that the men and women who made this all a reality will soon be gone, if they aren’t already. That’s not to ignore the lives lost in achieving that goal — not just the crew of Apollo 1 but those lost in other incidents – all, even had they not gone into space, still did their jobs well to get us where we would be.

The events of that amazing period in the late 50’s through to the 70’s will be nothing but audio and video records, museum pieces, and some old equipment left on the Moon and in Solar Orbit. Even the memories will be gone with all of those who experienced it, but the fact that we actually did it will never change.

As Neil said when he took that first step, it was indeed one “small step for [a] man” but for the human race, it was one leap forward that soon will happen again, and as we begin again in a much different environment than the one the last “Space Race” started I can only hope those in the future will understand and appreciate the incredible event that was not just Apollo 11, but everything all of humanity did to get us to the point we’re at, and beyond.

Right, this was supposed to be about Apollo 11. Well, I guess it was, in such a sense of what came from it, and how for as much as most of the world knows of the event, very few really know everything surrounding it, and how much changed because of it.

Once again, another as I felt at the time flood of actual thoughts and emotions. I’ll have to say I’m both incredibly happy and sad at this time — an odd mix, but the thoughts above are genuine. This is what thinking about Apollo 11 and the side effect of its success brings to mind, so, take it for what it is.

Thank you for reading if you’ve made it this far. I appreciate it more than you know…