Early in the morning of April 4th, 1968, on launch pad 39-A at the Kennedy Space Center, the second Saturn V rocket to fly was launched. This mission was Apollo 6 – another unmanned test of the Saturn V and the Apollo Command-Service module, much the same as the Apollo 4 mission in November of 1967.

While this was planned to be another by the books flight, in practice it was anything but.

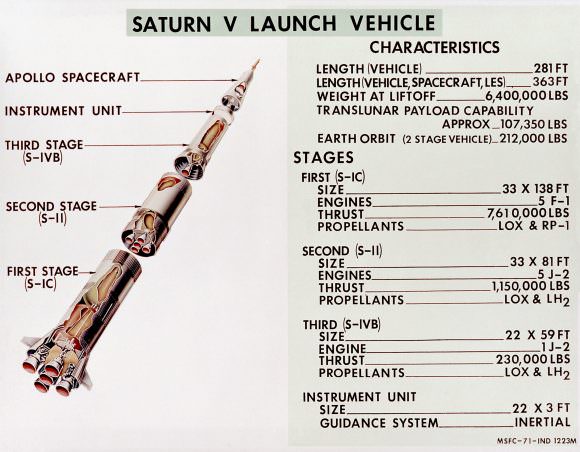

Problems developed immediately after launch. A phenomena known as “Pogo oscillation” developed as the vehicle rode on the 7.5 million pounds of force generated by the Saturn V 1st stage, known as the S-1C. This effect is basically similar to that of a pogo stick – a repeated increase in the thrust of a vehicle due to how fuel is being forced into the engines by the oscillation itself, eventually risking destroying the vehicle if unchecked. If you’ve ever shaken a bottle of something to get all of the fluid inside to come out, then you kind of get the idea.

That alone would be rather bad, and could cause for an abort of the launch if this were a crewed flight. Things got worse from there, though.

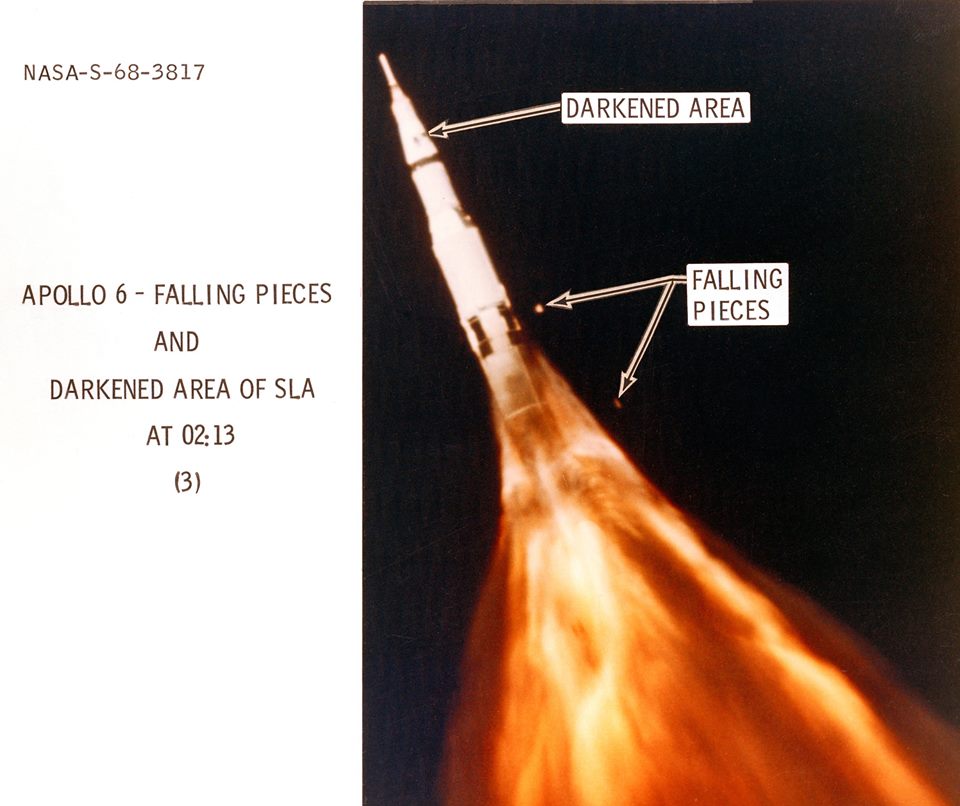

The Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter – the set of 4 panels underneath the Command-Service module that house the Lunar Module during ascent began to develop holes. Large chunks of lightweight paneling began falling away in about the 1st or 2nd minute of flight! This too would have likely been an abort scenario had a crew been on this mission, but, being a test flight, NASA pressed on.

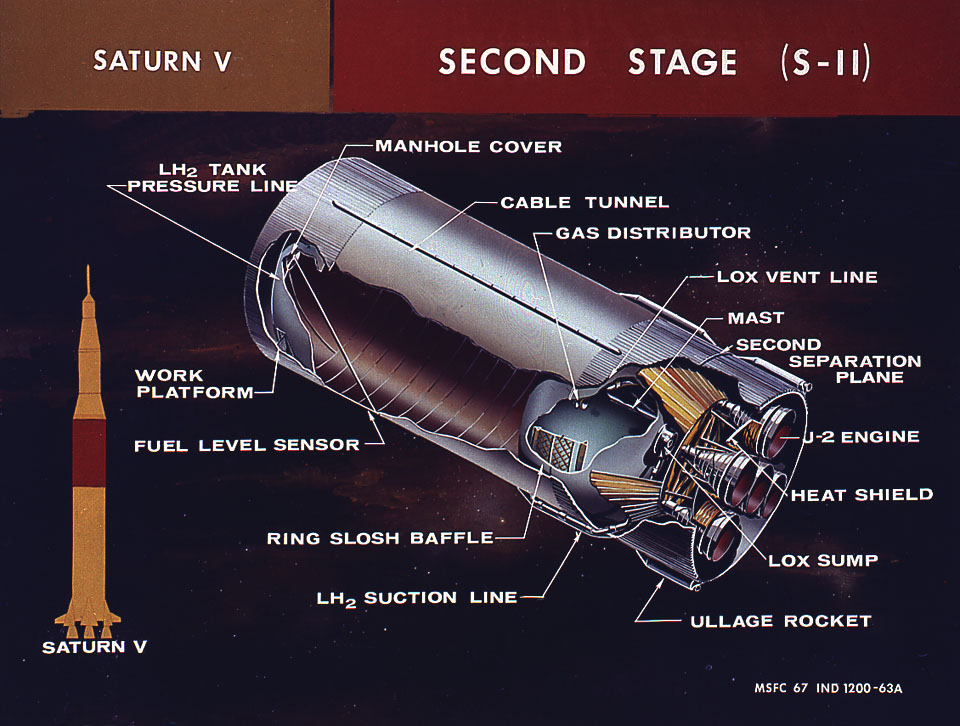

2 and a half minutes in, the 1st stage had done its job and was jettisoned – the Saturn V second stage, the S-II, was ready to take over. A relatively smooth ride compared to the S-1C, the S-II was usually the point where things got (relatively) relaxed in later launches. For Apollo 6, it would prove the most intense moment of the flight.

About 3 and a half minutes into the burn of the S-II, engine 2 of the 5 on the stage began to develop problems. About 2 minutes later, the engine would be outright shut down by the Instrument Unit – a computer system that controlled the vehicle during launch – on the Saturn V. Just seconds later, another engine would shut down on the S-II, an engine that had nothing wrong with it.

It turns out, the first engine had developed a leak in an oxygen feed line for the igniter system of the engine – this pushed more oxygen into the engine than it was designed to operate with, causing a loss of pressure which the Instrument Unit saw as a reason to shut down the engine. The Saturn V could still make it to orbit on fewer engines by firing those engines for longer, but the shutdown of the other engine made no sense.

Or, it wouldn’t until it was discovered that there was a crossed wire, and the signal that shut down the damaged engine actually shut down that good engine, leaving the S-II with only 3 engines to limp towards orbit with, having to burn nearly a minute longer than normal to achieve its goal.

No other problems developed with the S-II and it finished its job. The Saturn V 3rd stage, the S-IVB, took over and pushed Apollo 6 into orbit. The S-IVB experienced its own performance issues and had to burn slightly longer as well, putting Apollo 6 into a 93.49-nautical-mile (173.14 km) by 194.44-nautical-mile (360.10 km) parking orbit, instead of the planned 100-nautical-mile (190 km) circular orbit.

2 hours later the S-IVB was instructed to fire again, to put Apollo 6 into a high elliptical orbit so as to test the ability for the Saturn V to put a spacecraft on a trans-lunar trajectory, as well as test the heat shield of the Command Module to the temperatures expected on a return from the Moon.

The S-IVB failed to restart. It was decided to use the Apollo Service Propulsion System to insert the Command/Service Module into the target orbit. There wouldn’t be enough fuel to increase the speed of the vehicle to that of a re-entry from the Moon, but this was already proven in Apollo 4 and was deemed unnecessary. Interestingly, the SPS burn was longer than would ever be needed on an actual flight, and this proved the long-duration burn reliability of this critical engine.

Apollo 6 Preflight Briefing – 1968 NASA Film

The Apollo 4 command module would splash down just shy of 10 hours after launch, successfully completing its mission, albeit in the most odd of ways. The Command module itself was hybridized from 2 other spacecraft, Apollo CM-14 and Apollo CM-20, and in a bit of uniqueness that helps identify the craft, the Service Module was the only one on a Saturn V to ever be painted white, rather than left silver in color.

The mission was still, despite all the errors, a success. The Pogo problem was never solved, but steps were put in to help try to alleviate the issue in future flights. The S-II fuel line issues were studied and solved by a minor fuel line design change, and no S-IVB ever failed to re-ignite on a future Saturn V flight.

NASA was ready, not only to fly a manned mission in Earth orbit on Apollo 7, but for a manned Saturn V flight on Apollo 8.

Events soon to unfold in the Soviet Union would change the mission of Apollo 8 quite a bit between now and its launch time, but that’s a story for another day. More to come, as always.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_6